The Lure of the Eternal City in 18th Century Britain

Four exceptional objects trace Britain’s enduring fascination with Rome in the eighteenth century, a city that served both as a repository of antiquities and as a crucible for new artistic ideas.

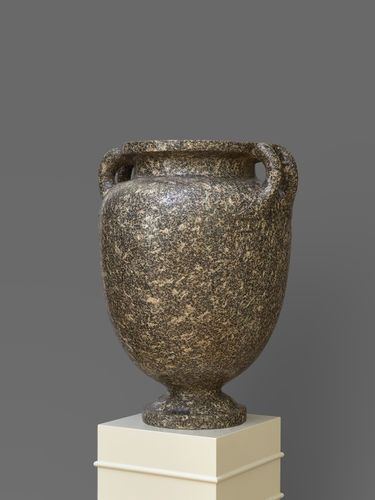

At its heart is a remarkable rediscovery: an unpublished vase originally created for Nero’s (37–68 AD) Domus Transitoria on the Palatine Hill, the precursor to the emperor’s famed Domus Aurea. Excavated in 1721 on lands belonging to the Farnese Family, the vase was soon acquired by William Ponsonby, 2nd Earl of Bessborough (1704–1793), one of the most distinguished British collectors of antiquities. It was recorded in the 1801 sale catalogue of the Bessborough collection at Parkstead House, where it was purchased by Frederick Howard (1748–1825), 5th Earl of Carlisle, and remained at Castle Howard until its sale to a major American collection in 2015. The vase thus appears on the market now for only the third time in its nearly two-thousand-year history.

The exhibition continues with the Hope Roma, a commanding head of the personification of the city of Rome, executed by the Neoclassical sculptor Vincenzo Pacetti (1746-1820). The work derives from an antique model formerly in the Borghese collection and now in the Louvre. Camillo Borghese granted Pacetti permission to carve a copy in 1783. The sculpture was then acquired by Thomas Hope (1769-1831), who installed it in his celebrated Sculpture Gallery at 10 Duchess Street in London, one of the earliest art galleries open to the public in Europe.

Immersing us in the architectural setting of the Eternal City, a large-scale painting by Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765) hangs in the main gallery depicting A Capriccio of the Roman Forum with Tuccia, the Vestal Virgin. Realised in 1731, this remarkable landscape is one of the most ambitious and densely populated examples of the Roman ‘capriccio’ by the undisputed master of the genre, featuring nearly 80 figures alongside many of the city’s antiquities. The signed and dated painting was acquired by the Grand-Tourist Robert Jones of Fonmon Castle (1706–1742), Glamorganshire, during his stay in Rome in 1730–31 as part of a significant group of works he assembled there. Remarkably, this is one of the few paintings to re-emerge on the market after nearly three centuries retaining a single, continuous provenance since its purchase in the early eighteenth century.

Joseph Plura (1724-1756), Bust of Gratiana Davenport, 1753

Joseph Plura (1724-1756), Bust of Gratiana Davenport, 1753

Completing the display is the Bust of Gratiana Davenport (1710-1773), one of only two known works in marble by Joseph Plura (1724-1756), a Turin-born sculptor active in England. The bust constitutes a considerable addition to the artist’s oeuvre. As it represents the sitter dressed in ancient Roman garb, it displays the ways in which the spirit of the Grand Tour enlivened the lives of patrons in Georgian England. Commissioned in 1753, it has remained in the sitter’s family ever since and was on long-term loan to Lacock Abbey (National Trust) until October 2023. It is offered on the market here for the first time.

The exhibition expands on the themes of the conference, Academy, Market, Industry. Sculptural Models, Themes, and Genres between Britain and Italy, c. 1728–1854, sponsored by the gallery and organised at the Victoria and Albert Museum on 16-17 May 2025. Together, these works trace the circulation of artists, objects, and ideas between Italy and Britain: from an imperial commission in Nero’s Rome, to the studios of Neoclassical sculptors, to the homes and galleries of Grand Tour collectors.

The show underscores how provenance remains a crucial repository of cultural and financial value, where the histories of ownership and movement are as significant as the objects themselves.